Barn Compost Heat Recovery - Thermo-Economic Analysis

This analysis was performed with Engineering Equation Solver (EES), a non-linear equation solver that includes various resources for thermodynamics, heat transfer, unit handling, and economic functions.

Download the Thermo-Economic model here to see the code for yourself.

Introduction

Generating heat for water and buildings can be energy intensive, especially in climates facing extreme winter weather. These energy needs are commonly met by natural gas water heaters for hydronic heating. An alternative heat source, the compost water heater, was developed in the 1970s by French inventor Jean Pain [1]. Compost heating systems recover waste heat generated during the decomposition process of organic materials. Implementation presents a potential for cost savings by reducing typical energy consumption.

This analysis evaluates the economic impact of modifying a natural gas-powered hot water floor heating system used in a livestock barn, with a compost heater.

The compost heater needs to be evacuated and replenished with new raw material as decomposition of the initial material slows and eventually stops. The modified system in this analysis operates on an 8-month evacuation and replenishment cycle [2]. After 8 months, the finished compost can be resold at an increased cost for fertilization [3]. Labor costs for evacuation and replenishment of the system are accounted for in the economic analysis.

The following discussion will highlight the assumptions made throughout the analysis, followed by an outline of our thermal and economic investigation. Lastly, a conclusion is presented with final thoughts.

Assumptions

Several assumptions were made in our system analysis:

- For winter months, Tsa = Ta, due to the less intensive solar effect on sol-air temperature.

- Pressure inside the water tank is assumed constant.

- The barn roof and floor are perfectly insulated.

- Ventilation load and humidity can be ignored.

- The building model capacitance can be ignored.

- The heated floor temperature does not drop below the barn temperature when the ambient temperature is higher than the zone (system does not model cooling to maintain barn zone temperature).

- Heat loss from the barn is equal to the heat into the barn (no storage).

- Water and air are modeled as real fluids with a design condition of -20 F ambient and 50 F barn temperature.

These assumptions create a worst-case scenario in our reference design, signifying a lower limit to system performance and energy savings.

Thermal Analysis

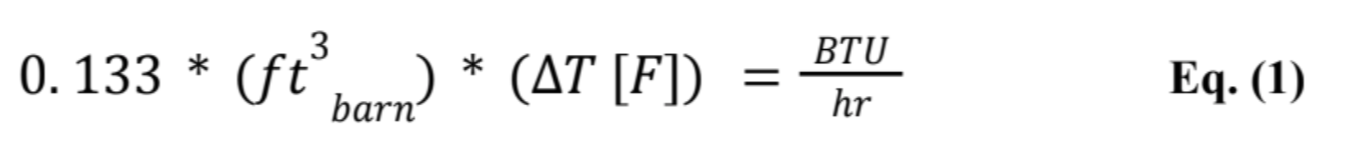

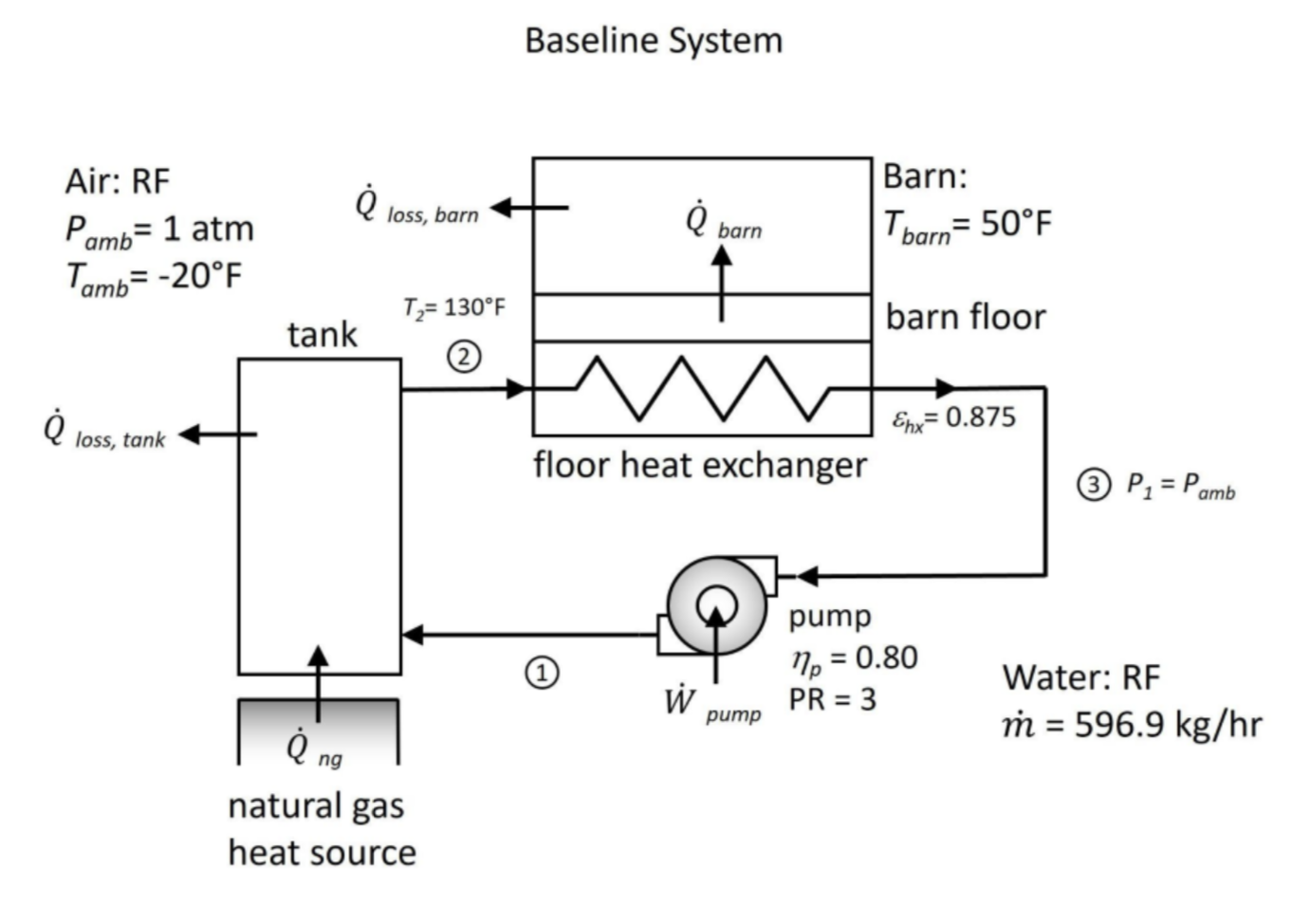

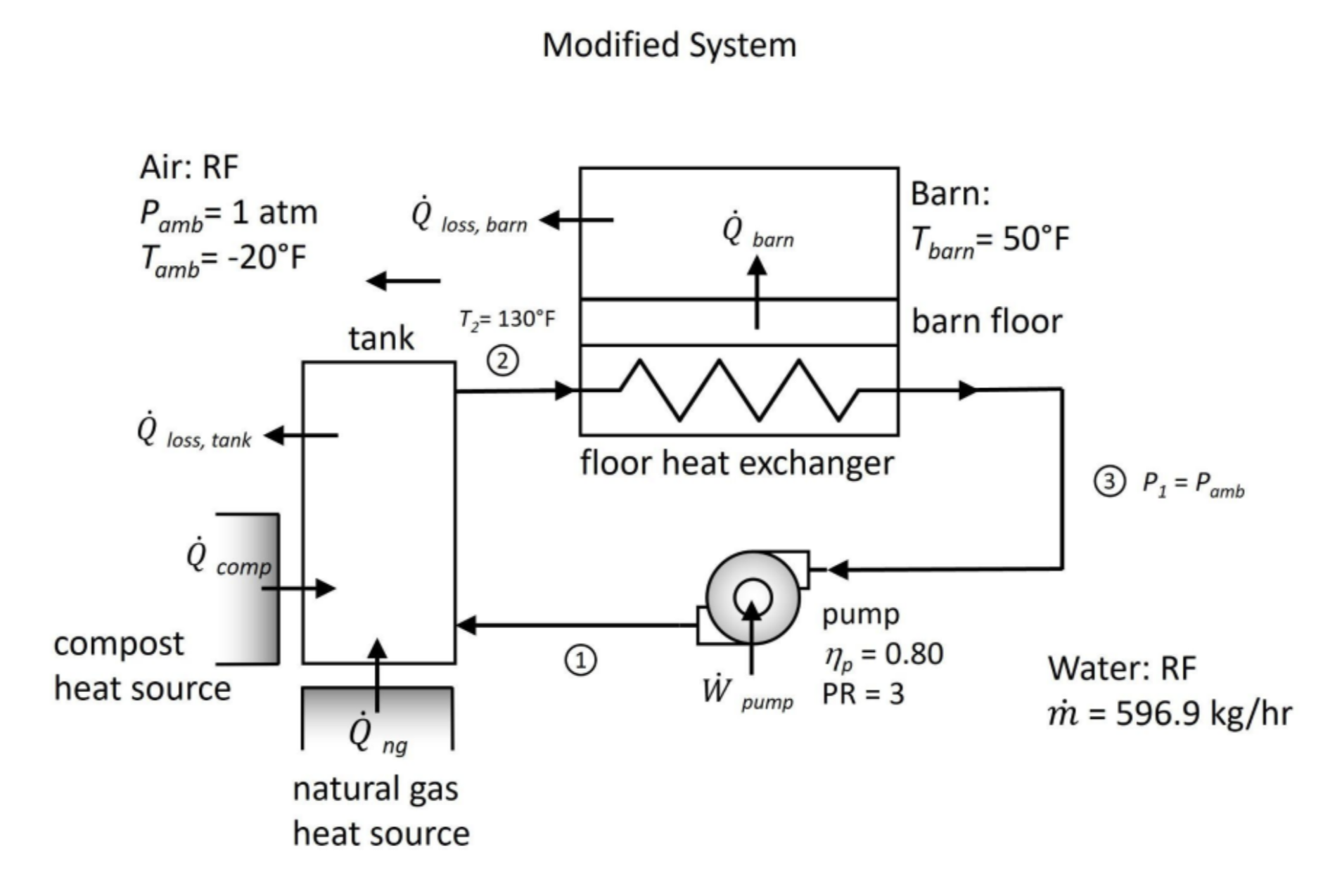

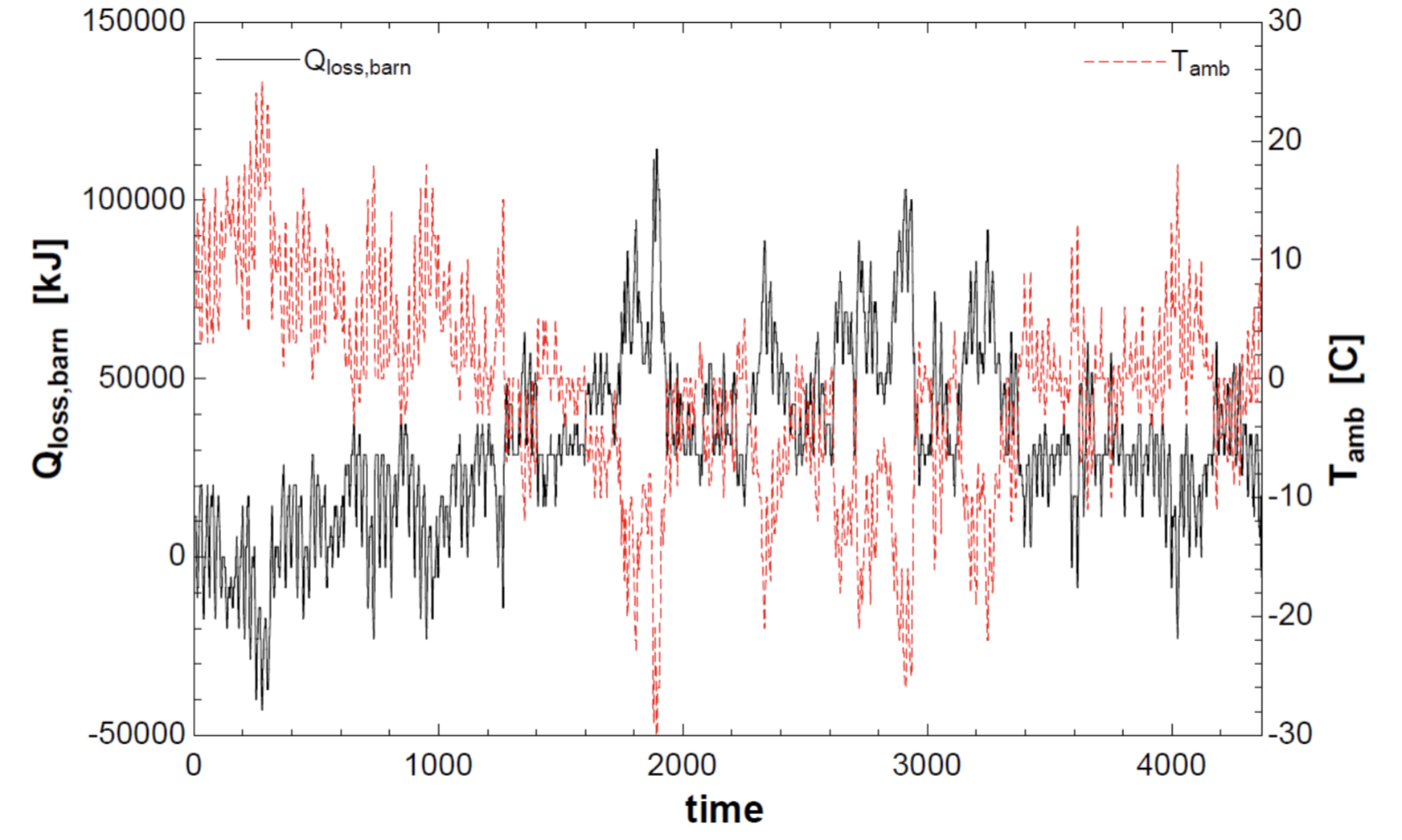

Diagrams for the baseline and modified systems are shown in Figures A.1.1 & A.1.2. The driving load for both systems is barn heat loss to ambient, indicated in Figure A.5.1. Heat loss was first estimated using Eq. 1, which predicts barn heating requirements [4].

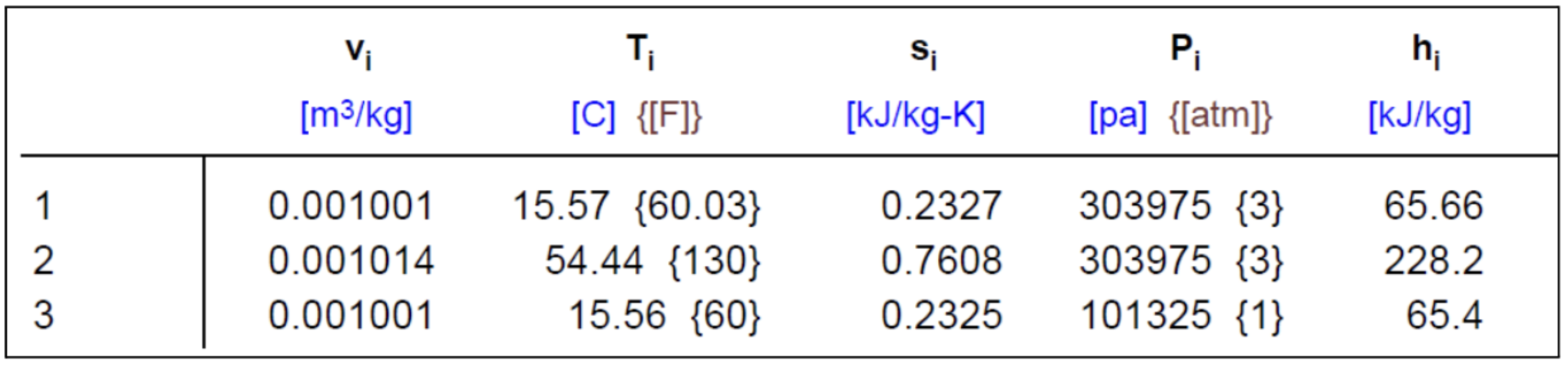

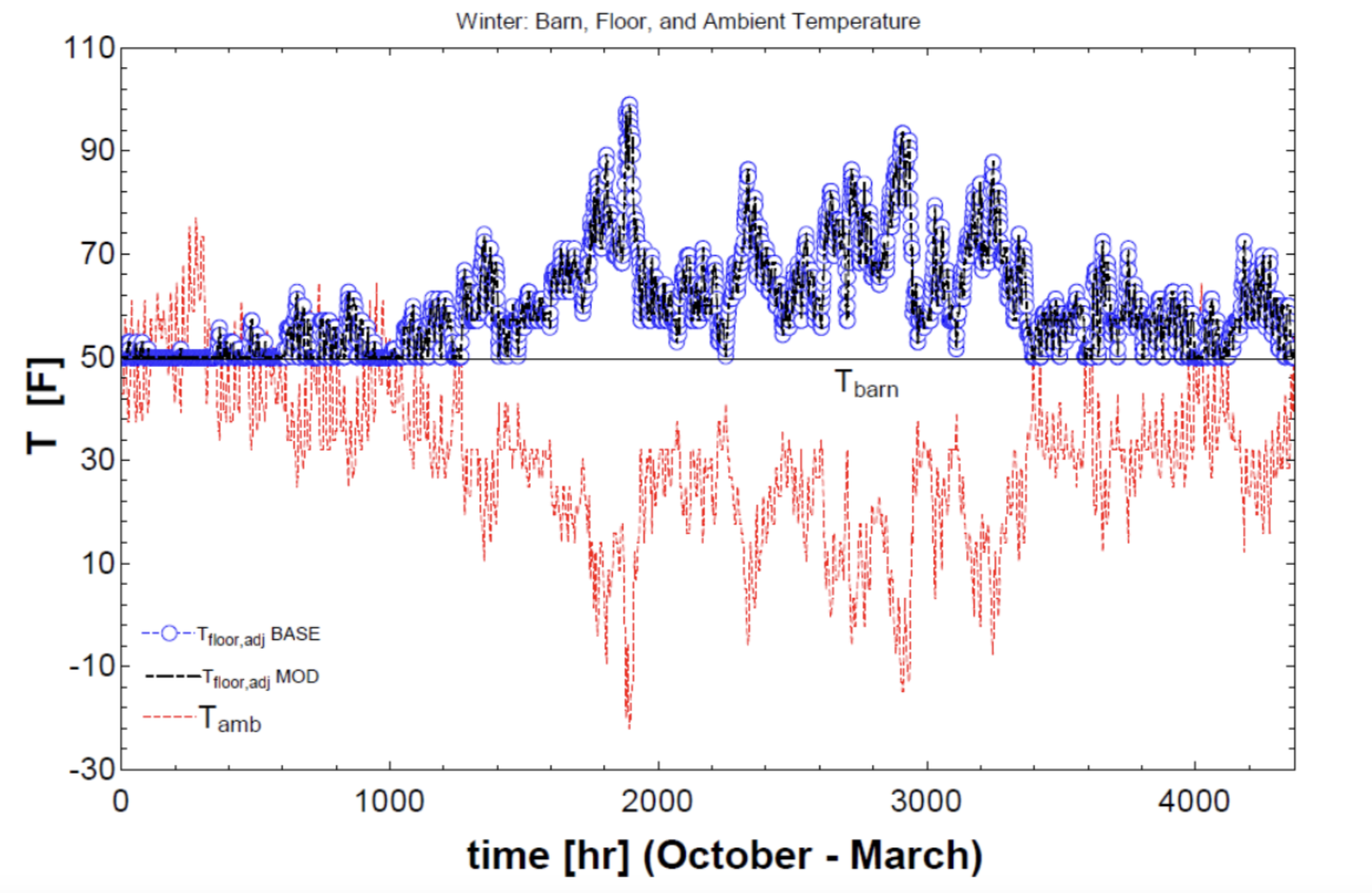

This value was validated (error ~ 6%) using a building model calculation based on convection and conduction resistance networks. The barn is modeled as an uninsulated Hi-Rib Steel building with dirt flooring and 29 [ga] walls [5]. Design parameters are shown in table A.2.1. Conduction through the dirt was implemented to determine the required floor temperature at off-design conditions over the heating months (October-March), shown in Figure A.5.2. Operating parameters and diagrams for the design condition are documented in Appendix A.4.

The motivation for the system modification is to reduce unrestrained heat transfer through temperature differences. Specifically, the unrestrained heat transfer of the heat produced in the compost production. This would otherwise be wasted heat but is recuperated by the system to reduce the natural gas needed to heat the barn to the desired temperature.

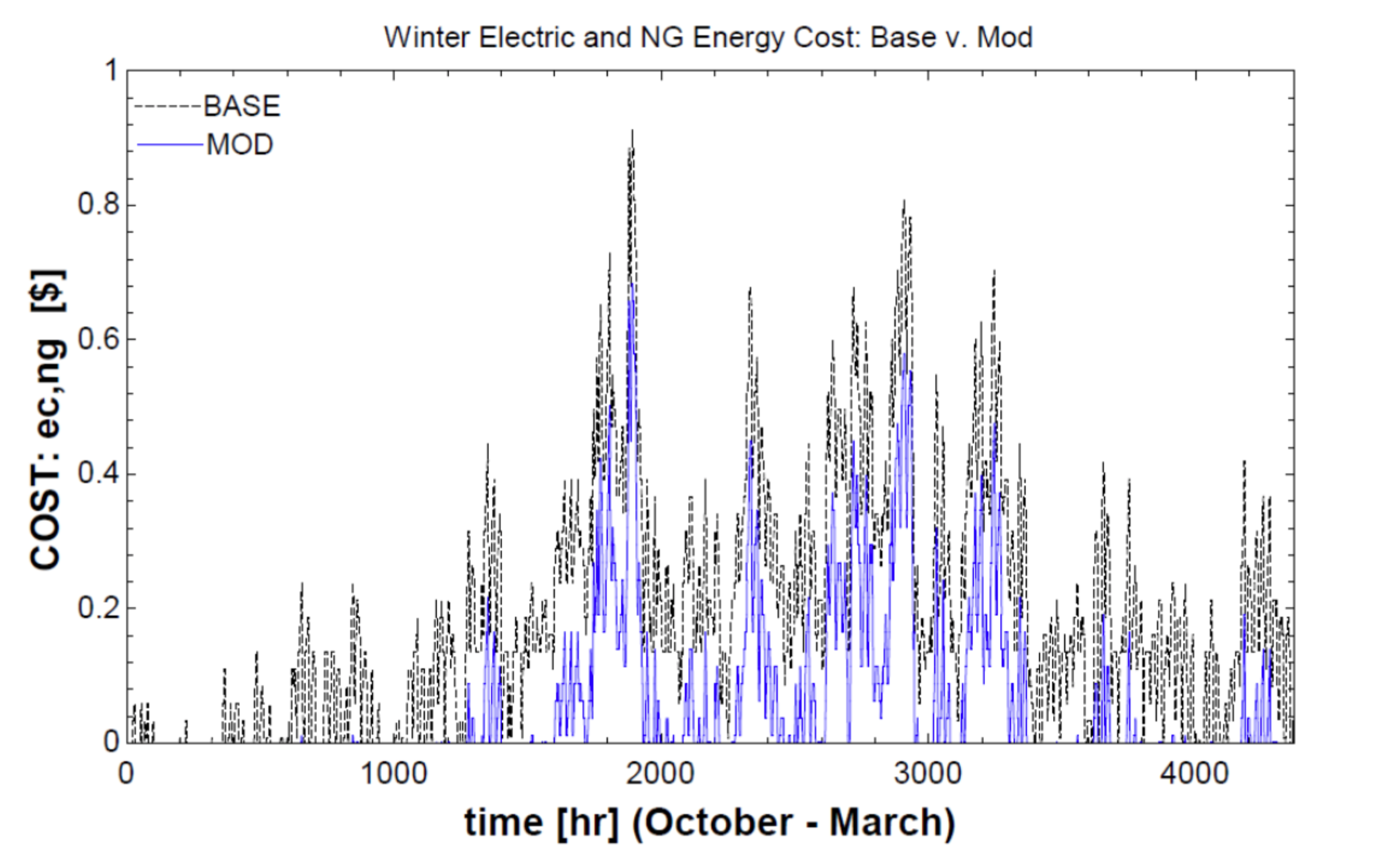

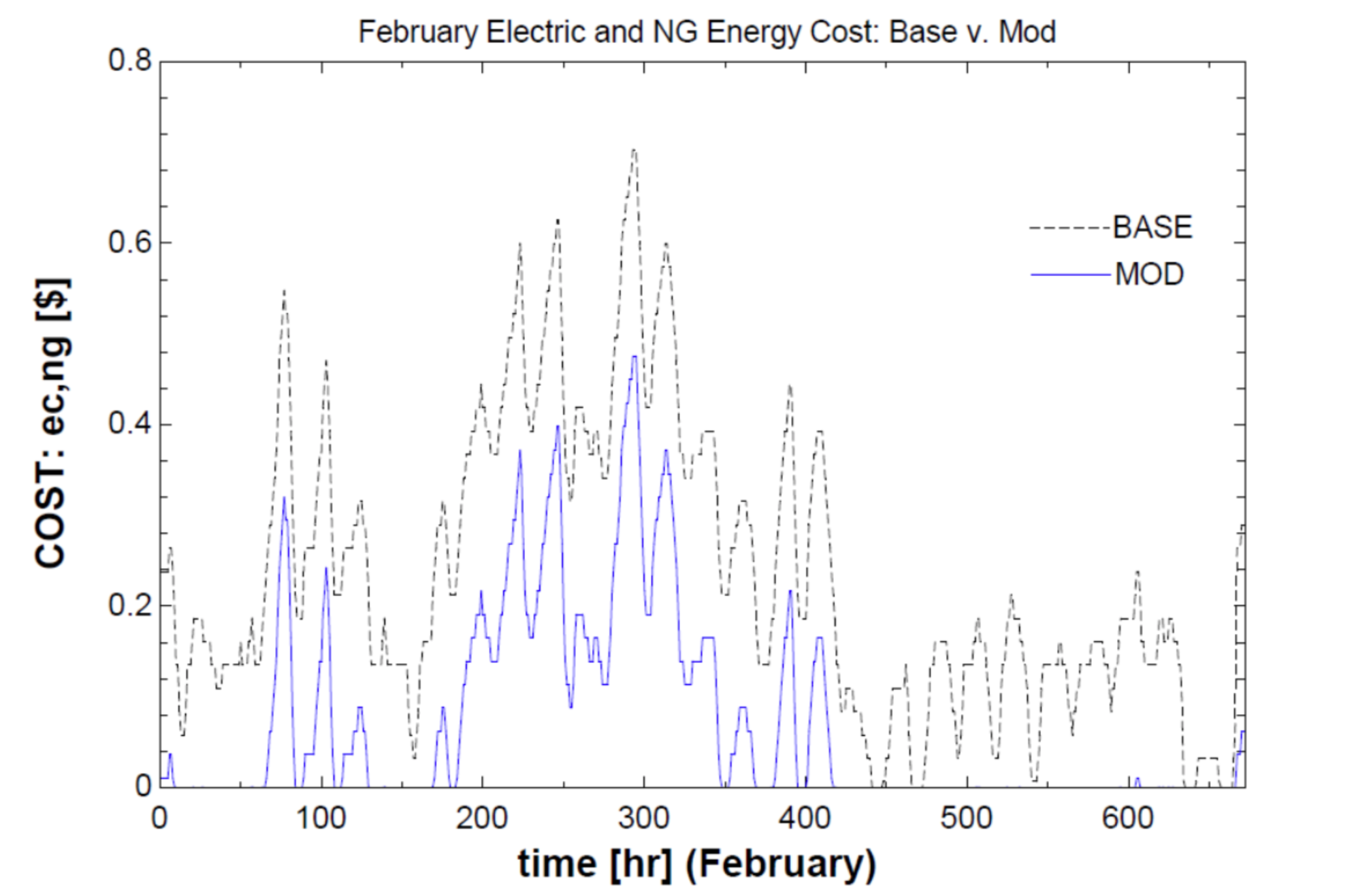

The energy savings in the modified system is 65.82 [GJ] over the course of the winter season [6]. This represents energy savings through the reduction of natural gas burned and required pump power. Figure A.5.3 indicates the total energy cost required to maintain the barn at the setpoint temperature, which also represents the winter energy savings. Notice that early in the heating season, the heat supplied from the compost heater is satisfactory due to higher ambient temperatures. Thus there is no energy cost for the modified system for many hours of the study. A higher resolution plot is shown for February in Figure A.5.4. These energy savings, minus compost purchase and install cost, combined with the effective fuel cost subsidization by means of compost fertilizer resale, motivate the system modification.

Figure A.1.1: Baseline barn heating system.

Figure A.1.2: Modified barn heating system.

Economic Analysis

The economic viability of the modification was accomplished by calculating the Life Cycle Savings (LCS) of the modified system relative to the base system with N = 10. Parameters used in the LCS analysis are provided in Table A.3.1. Results of the analysis with denoted figures of merit are shown in Figure A.6.1.

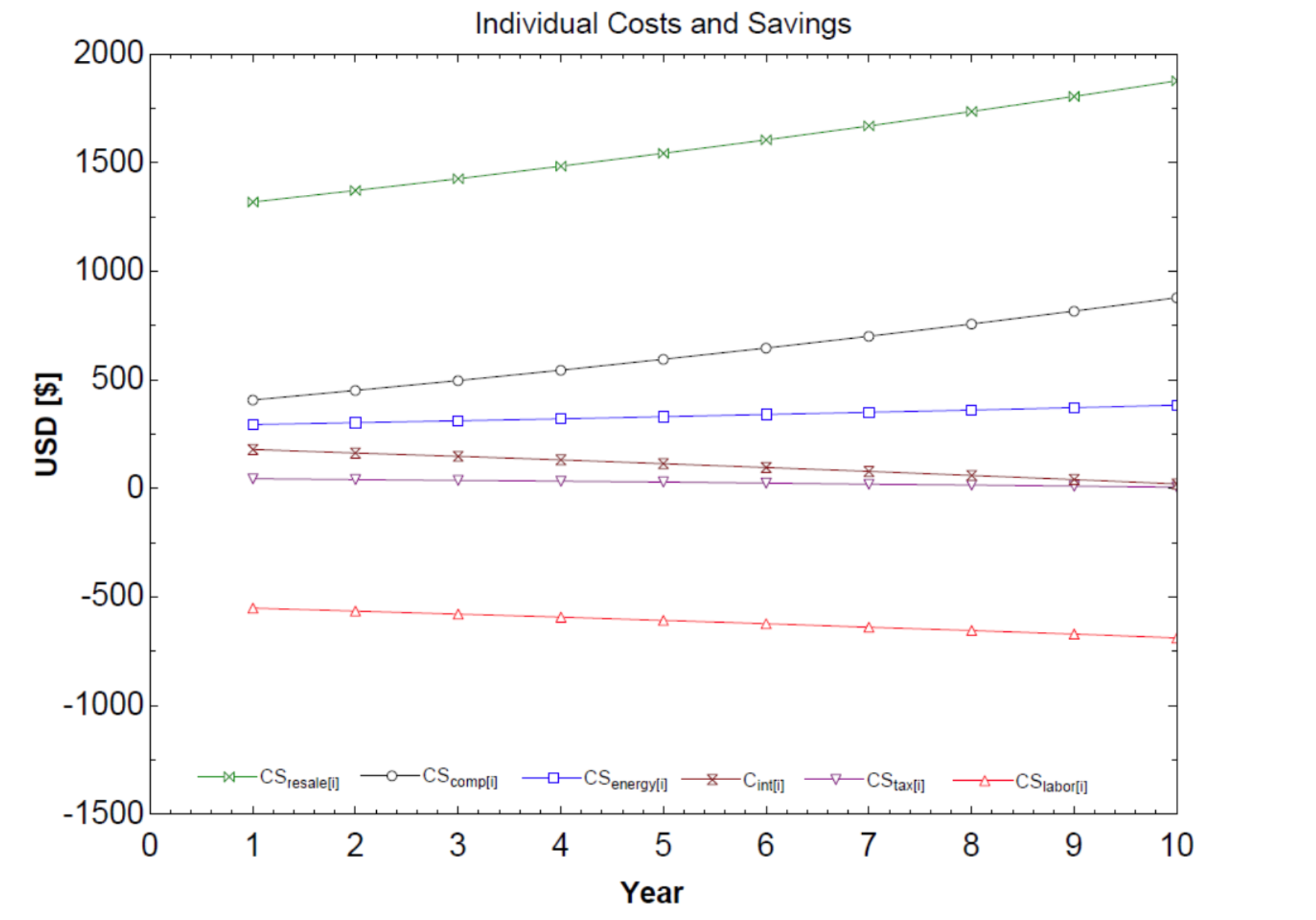

LCS analysis indicates that the modified system is economically viable and outperforms the base system during a parametric study of off-design conditions over several winter months (October-March) by a considerable margin. The maximum initial investment for the modified system at which the LCS = 0, is $11,413; a considerably large budget for the simple implementation of an insulated compost container with piping. With a set modification capital cost of $7000 [7], the LCS over the 10-year period is $4,364. At the end of the first winter heating season, a 70.29% energy (natural gas and electric) cost savings ($250.5 vs. $843.2) is achieved in the modified system. These savings come from a shift in the energy used from a natural gas heater to a compost heat source. Utilization of compost heat further reduces operating costs due to the higher resale value of the fertilizer at the end of each extraction period, compared to its annual cost [3]. Note that the compost need not actually be sold if the farmer will use it to fertilize crops. Thus, the resale value could act as a separate cost avoidance. Figure A.6.2 shows the costs and savings for each respective component. Additionally, the ROI of the modified system is 0.1519 when LCS = 0, which is much larger than the market discount rate used in our model, 0.025.

Finally, an uncertainty analysis of several parameters acting on the value of the LCS and ROI was conducted. This analysis was performed by assigning uncertainties to each variable and solving for the percent of total uncertainty they individually represent. Results are summarized in Tables A.6.1-3. Results from the ROI study indicate that the projected ROI of the modified system is most sensitive to variation in labor cost (to evacuate/replenish the compost) and the inflation rate of compost fertilizer that can be salvaged each season. Similar to the ROI analysis, uncertainty analysis on the LCS shows heavy dependence on the compost purchase fraction, the cost of compost fertilizer salvage that can be sold each season, and variation in labor cost.

Conclusion

Thermal and economic analysis of the proposed barn heating system indicate that modification through compost heater installation is feasible and profitable. Profitability is largely dependent on the user’s need for fertilizer, ability to resell fertilizer effectively, and the amount of compost used relative to the building size.

Table A.2.1: Parameters for base & modified system thermal performance.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Tank Depth | 2 [ft] |

| Tank Height | 6 [ft] |

| Barn Width | 30 [ft] |

| Barn Length | 40 [ft] |

| Barn Height | 10 [ft] |

| Steel Siding | 29 [ga.] |

| Dia_pipe | 0.75 [in] |

| Depth Soil | 3 [in] |

| N_cattle | 20 [-] |

| Q_cattle | 700 [kJ/cattle] |

| m_dot_water_DESIGN | 596.9 [kg/hr] |

| Epsilon_hx_floor | 0.875 [-] |

| Q_compost | 1000 [BTU/ton] |

| f_volume_compost,volume_building | 0.1 [-] |

| T_bard | 50 [F] |

| R_barn_surface_exterior | 0.25 [hr-ft^2-F/BTU] |

| R_barn_surface_interior | 0.68 [hr-ft^2-F/BTU] |

| k_steel | 8 [BTU/hr-ft-F] |

| k_soil | 0.7 [BTU/hr-ft-F] |

| Q_natural_gas_DESIGN | 92333 [BTU] |

| Q_comp_DESIGN | 23972 [BTU] |

Table A.3.1: Parameters for base & modified system economic performance.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Years of Analysis | 10 [years] |

| Market Discount Rate | 0.025 [-] |

| Tax Rate | 0.25 [-] |

| Modification Install Cost | 7000 [$] |

| Down Payment Fraction | 15 [-] |

| Mortgage Rate | 0.03 [-] |

| Compost Materials Cost | 25 [$/Ton] |

| Compost Resale | 55 [$/Ton] |

| Labor | 23 [$/Ton] |

| Electric Cost Inflation | 0.03 [-] |

| Compost Inflation | 0.03 [-] |

| Fertilizer Inflation | 0.04 [-] |

| Fraction of Compost Purchased | 0.05 [-] |

Results

Table A.4.1: State Properties: Design Cond

Figure A.5.1: Winter Hourly Heat Loss & Ambient Temperature Data: (Off-Design)

Figure A.5.2: Winter Hour System Temp Data: (Off-Design) Base & Mod System

Figure A.5.3: Hourly Winter Energy Cost (Off-Design) Base & Mod System

Figure A.5.4: February Hourly Energy Cost (Off-Design) Base & Mod System

Figure A.6.1: Economic Performance on 10 year model with Figures of Merit.

- A) Time when cash flow becomes positive.

- B) Time when cumulative fuel savings (including compost materials) = initial investment. (NOT ON PLOT: cumulative fuel savings impacted by annual compost and labor costs)

- C) Time when cumulative total savings = 0.

- D) Time when cumulative total savings = down payment.

- E) Time when cumulative total savings = remaining principal.

Figure A.6.2: Resale, System, Energy, Interest, Tax, and Labor Costs/Savings

References

[1] M. Feineigle, “The jean pain way,” The Permaculture Research Institute, 10-Dec-2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.permaculturenews.org/2011/12/15/the-jean-pain-way/. [Accessed: 05-Aug-2021].

[2] “Compost power!,” Cornell Small Farms, 17-Jun-2021. [Online]. Available: https://smallfarms.cornell.edu/2012/10/compost-power/. [Accessed: 05-Aug-2021].

[3] B. Faucette, “Doing the dirty work,” Waste360, 23-May-2011. [Online]. Available: https://www.waste360.com/composting-and-organic-waste/doing-dirty-work. [Accessed:05-Aug-2021].

[4] Farmer Boy. 2021. How To Select The Right Heater For Your Barn. [online] Available at: https://farmerboyag.com/blog/how-to-select-the-right-heater-for-your-barn/ [Accessed 5 August 2021].

[5] Morton Buildings. 2021. Pole Barns, Horse Barns, Metal Buildings. [online] Available at: https://mortonbuildings.com/projects/livestock/lael-jean-holdings-llc [Accessed 5 August 2021].

[6] Professor Michael Cheadle, “Madison Weather Data as a Function of Hour of the Year” Typical Meteorological Year Excel datasheet, [Accessed 5 August 2021].

[7] K. Pitschel and E. Lowry, “Gibbs House Compost Heat Recovery System,” 2016. Available at: https://wmich.edu/sites/default/files/attachments/u691/2016/LowryPitschel1.pdf [Accessed 5 August 2021].